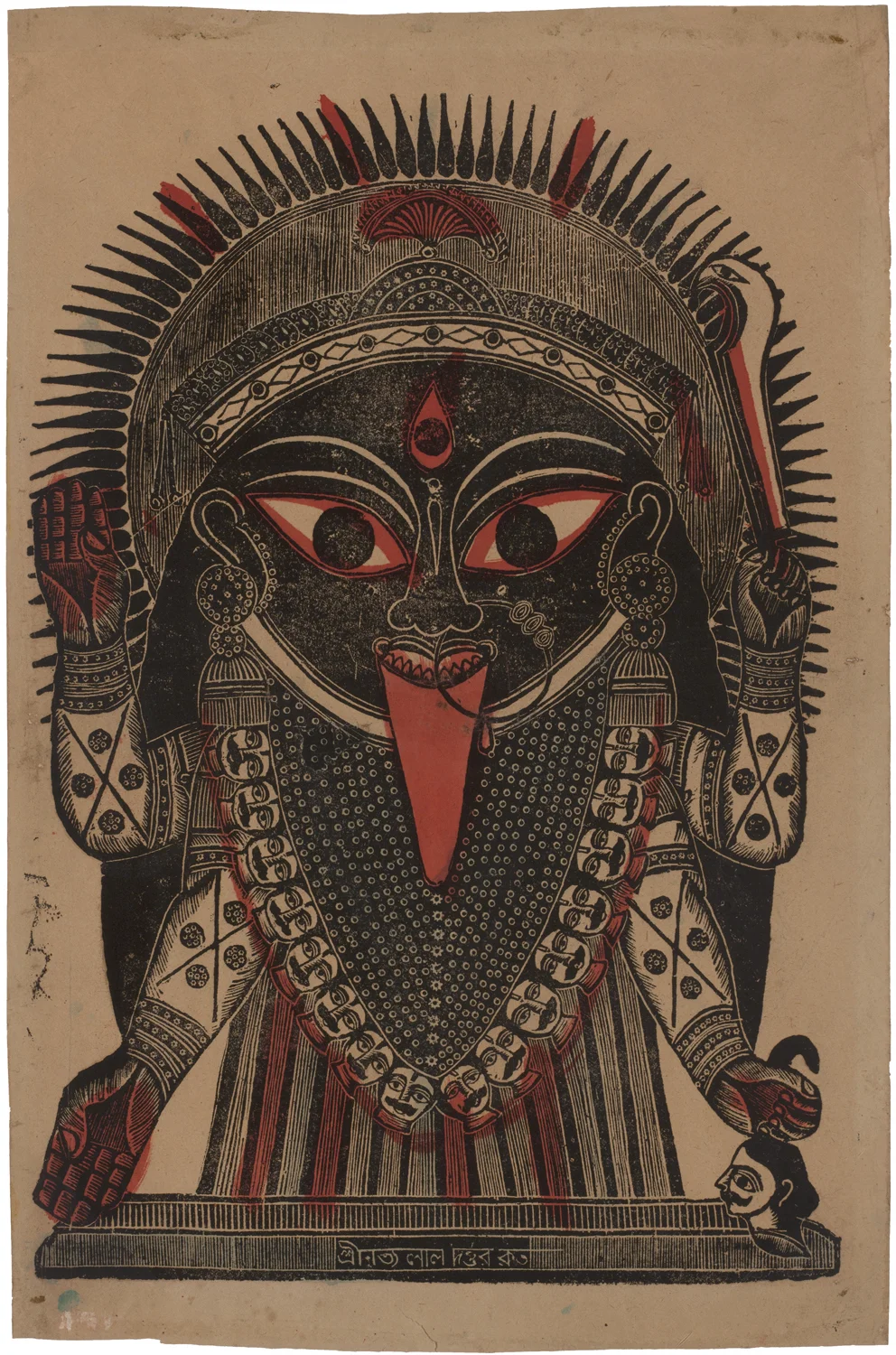

Nritya Lal Datta, Kali (ca. 1860–1870), woodblock print, 16 1/2 x 10 7/8 inches, Calcutta. Collection of Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté.

By Faye Hirsch

On the subcontinent, Indian lithographs of the gods are displayed everywhere, from temples to taxicabs, and revered by millions as a means to darshan, or communion with the gods. Unschooled Westerners have long regarded these bright, colorful images with their vivid stories as borderline kitsch, but increasingly, over the last decade or so, they have been collected and shown in the U.S., largely through the efforts of New York–based print publishers Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté.

The first of these lithographs—still immensely popular in offset or digital iterations—dates back to the third quarter of the 19th century, when the first Western-style workshops were set up in Kolkata (Calcutta). Today old lithos in fine condition are rare, given their hard use and an unpropitious environment that inflicts heavy humidity and paper-destroying insects. Linking indigenous traditions of worship with Western-style production, and mixing Hindu scriptural content with Western representational and narrative modes, the lithographs testify to complex relationships both economic and cultural.

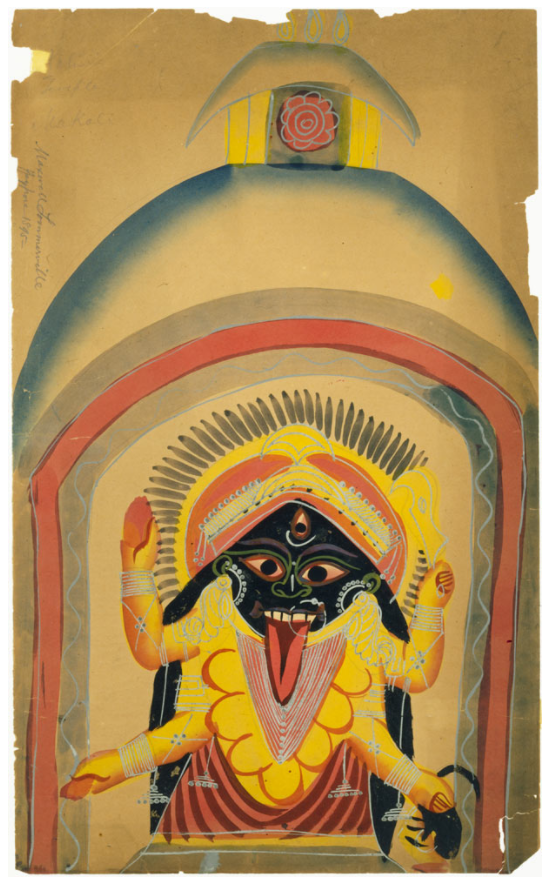

Kali (ca. 1880), lithograph with additions by hand, 7 7/8 x 6 inches. Published by P.C. Biswas, Calcutta. Collection of Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté.

Before the lithographs, however, there were woodcuts. From around 1830, there existed in Kolkata a prodigious industry of woodcut printing. Artisans operated in the northern part of the city, where local publishing had taken hold, with most of their activity centering on book illustration. By the 1850s, large, single-leaf woodcuts—today called “Battala” woodcuts for the neighborhood where they arose—were being produced as cheaper versions of the (already inexpensive) watercolor paintings, called patas,1 which had been made from the early 19th century onward. At first created by rural artists influenced, many times removed, by late Mughal manuscripts, the patas were sold by their painters, the patuas, from stalls in the southern part of the city, in the area around the renowned Kalighat Kali Temple, which was (and is) an important pilgrimage site. It houses a much-venerated effigy of the powerful goddess Kali—the “black one,” embodiment of time, creation and destruction, among other forces—as well as a relic (the toes, in the form of a stone) of another deity, Sati. Produced quickly with a few swipes of the brush, the patas were purchased by worshipers as reminders of their pilgrimage, as well as sacred images in their own right. By the 1860s, woodcuts were being offered there for a fraction of the cost of the patas, whose imagery they often borrowed.2

Unfortunately, very few of the woodcuts have survived—one source, from 1983, counted a scant 100 known examples.3 The thin, poor quality paper made them even more vulnerable to damage than the lithographs.4 The heyday of these woodcuts was brief. By the early 1880s, production of both woodcuts and patas nearly ceased because of competition from the booming lithographic industry. More descriptive, colorful and detailed; cheaper, more easily disseminated, and printed in greater numbers, the lithographs were instantly more popular.5 Having arisen from demands not dissimilar to those for devotional woodcuts in Western Europe from the 15th century onward, the relatively crude Battala woodcuts died out much more quickly; their efflorescence lasted just a few decades.6

Baron and Boisanté had been smitten with Indian “god prints” on their first trip to the country in 2000; six years later they opened Om from India, to promote interest in these works, and also began amassing a private collection notable for its historical breadth and the unusually fine condition of its impressions.7 Although their primary focus has been on lithographs, in 2010 they saw for the first time a remarkable woodcut of Kali at the Museum of Indology in Jaipur. It was a composition they had seen in later lithographs but never in woodcut and they began searching for an impression. In 2014 they purchased their first woodcut, a hieratic image of Shiva, five-headed and four-armed, seated on a throne. One year later, they heard from a dealer in India who had managed to locate the Kali.

Kalighat painting on brown paper (ca. 19th-century), 18 x 11 inches. Calcutta. Courtesy of Penn Museum, image # 29-225-5. Bequest of Maxwell Sommerville.

At 41.9 x 27.7 cm and in near-perfect condition (it is adhered to a backing sheet as is typical), the Kali is an impressive image. Though Battala woodcuts of historical and social subjects are known, most are religious. Of these, there are two types: those with narratives, and “more iconic representations of Puranic divinities,” intended for mystical devotion, which constitute the largest number of prints.8 The Kali falls into the second category. It is ultimately based on the effigy in the Kalighat temple, a stylized sculpture of the goddess with black skin, three lurid red eyes, and a long tongue made of gold. She wears a crown and is often garlanded with flowers. Pilgrims circumambulate the figure in their devotions, making offerings. The stylized woodcut image shows Kali in a frontal, hieratic pose with four arms, as stipulated in sacred writings. She wears a crown, like the effigy, and radiates a dark light in the form of black spikes. Around her neck hangs a long necklace beaded with 16 severed heads. One tantric mantra (a written guide providing a vivid description for those who wish to commune with the goddess) formulates Kali as follows:

She is the terrible one with a dreadful face. She should be meditated upon as having disheveled hair and a garland of freshly cut human heads. She has four arms. In her upper left hand she holds a sword that has just been bloodied by the severed head that she holds in her lower left hand. Her upper right hand makes the gesture of assurance and the lower right hand, the sign of granting favors. She has a bluish complexion and is lustrous like a dark cloud.9

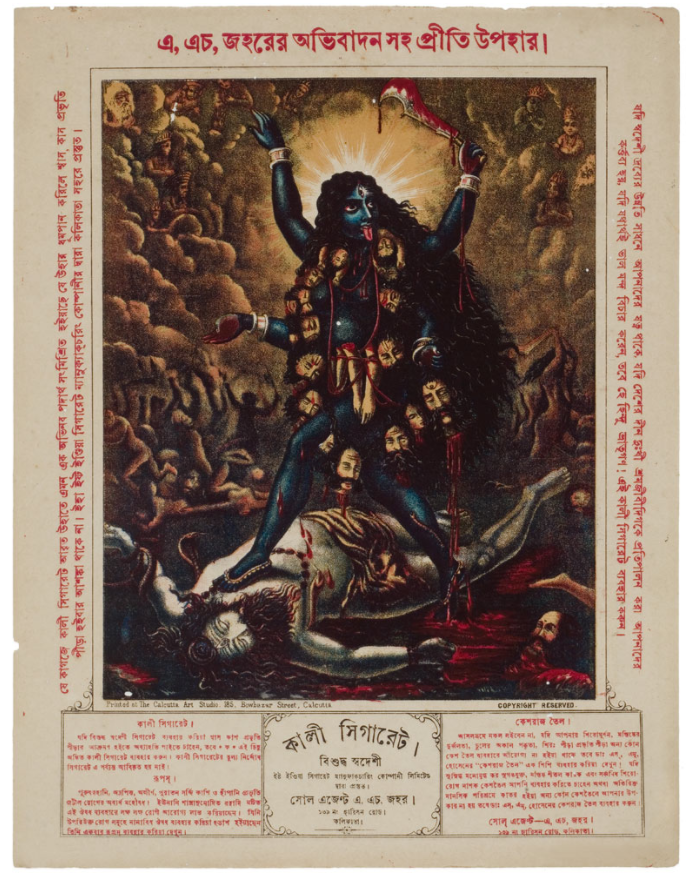

Kali (1883), lithograph with hand-coloring, 15 3/4 x 12 1/2 inches. Published by Calcutta Art Studio. Collection of Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté.

According to another tantric source, “She is lustrous like a dark cloud and wears dark clothes. Her tongue lolls, her face is dreadful to behold, her eyes are sunken, and she smiles.10 The tantric sources go on in great detail about the appearance and actions of the goddess, who is similarly fleshed out in the lithographic, narrative representations. In god prints, she can be seen treading on the supine figure of Shiva, her consort, who has fainted in terror, as if dead. Behind are vignettes of battlefields or cremation grounds. Kali’s mouth is open and her tongue always lolling to indicate her overweening appetites for violence and sex. Kali is a complex goddess, one of the most powerful in the Indian pantheon in her many manifestations, and she represents the forces of chaos and destruction. Raging, she terrifies those whom she wishes to defeat or seduce.

In the woodcut she is generalized and less terrible than in the narrative representations. Basic elements of scriptural descriptions are present, but certain details make no sense—as in the teeth that lie behind the tongue. Her large eyes are hypnotic, as if returning the gaze of the person worshipping her. A few swipes of red watercolor, hand-applied, concisely convey her bloody nature, as does her tongue (though it is gold in the effigy). As with all such frontal, hieratic representations—Eastern Orthodox icons, for example—this Kali is not subject to the vagaries of time, as she might be in a narrative, but instead stands still and measureless in her role as a prompt to meditate on the divine.

This print is one of just seven impressions that Baron has been able to locate in the world.11 It is the only one in the U.S. and this is the first time it has been published. Though printed from different blocks, the seven known Kali woodcuts differ only in small decorative details, suggesting a shared prototype to which the artists remained faithful, much like painters of Byzantine icons. The proto-type might well have been a pat, for a very similar hieratic Kali related to the Kalighat effigy is found in a number of delightful watercolor examples. The carving of multiple, similar blocks attests the importance of fidelity to the inspiring image, trumping fanciful flights of originality; it also implies the popularity of the image, which might have demanded large printings that wore out the blocks. (No blocks of any single-sheet Battala woodcuts are known to survive.)

Kali (ca. 1890), lithograph, 16 5/8 x 12 7/8 inches. Published by Calcutta Art Studio. Collection of Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté.

This Kali is signed in the block in Bengali, “created by Shri Nrityalal Datta.” (The name is sometimes transliterated as “Dutta.”) Datta’s signature is found in two other Kali prints—one at the Museum of Folk and Tribal Art in Durgaon, outside Delhi, and the other at the Delhi Art Gallery, a commercial gallery.12 A second artist, Benimadhab Bhattacharya, signed Kali prints located in the Victoria Memorial Museum, Kolkata, and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.13 Datta was one of the few woodcut artists who had his own printing establishment, producing books as well as single-leaf woodblock prints. He was the most prolific of the known artists, “the greatest perhaps of the woodcut artists of the time, with his extraordinary skill in filling empty spaces, the density and harmony of his compositions, and the grace of his forms,” as Purnendu Pattrea observes, adding that Datta was the only one of the Battala engravers to have a lasting effect on later artists.14 The sole in-depth book on the Battala prints, Ashit Paul’s 1983 Woodcut Prints of Nineteenth-Century Calcutta, in which Pattrea writes, reproduces some 14 of Datta’s prints. They vary in content and somewhat in style depending on the kind of scene they are representing—i.e., narrative or iconic, secular or religious. Among his subjects, for example, are a circus image, decorative birds and a scene gently lampooning a babu, or Indian functionary of a class that rose to prominence in the urbane international milieu of 19th-century British-ruled Kolkata. Imma Ramos has analyzed some of the printed imagery of colonial India as subtly encoding messages of resistance; among these were the severed heads around the necks of lithographic Kalis, resembling too closely for comfort the faces and coiffures of the overlord British. This fact “seems to have precipitated the drafting of the 1910 Press Act, which would rigorously control picture production and circulation in the first half of the twentieth century.”15 Kali, it seems, was always incendiary.

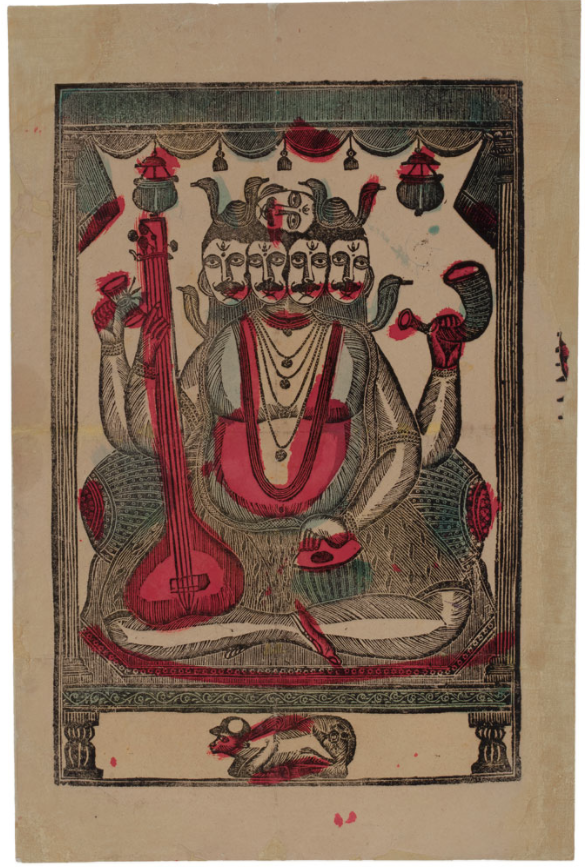

Nritya Lal Datta, Shiva (ca. 1860–1870), woodblock print, 17 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches, Calcutta. Collection of Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté.

Like most avid collectors, Baron and Boisanté delight in the dramatic near-misses and coincidences that occur in the hunt for prints. The very fact that they became so enamored of the Kali woodcut after seeing it just once and then managed to obtain so rare an object, is, to Baron, a matter of great satisfaction. However, a truly odd coincidence concerns a relationship between the only two woodcuts they own—the Kali and the Shiva. It is known that sometimes the Battala woodcut artists printed more than one image on a sheet—two, or four, carved into a single block—which were then cut down to be sold separately. At the far right of their Shiva is a detail that only the most devoted aficionado of Battala woodcuts would be able to recognize. It is the tiniest shard of a hand, colored red, with a few spikes behind it—evidence that the Shiva once shared its sheet with a Kali just like the one in Baron and Boisanté’s collection. It happens that the Museum of Indian Folk & Tribal Art in Gurgaon, outside Delhi, also owns the same woodcuts of Shiva and Kali (the latter, as mentioned, signed by Nrityalal Datta). Looking closely at the reproductions in the museum’s publication Masterpieces of Indian Folk & Tribal Art, Baron noted symmetrical water damage in the museum’s two prints and ascertained that they were once united and later cut apart.16 In other words, although Baron and Boisanté’s two woodcuts were not impressed on the same sheet, they were printed from the same block within an edition of double-image prints in which Shiva and Kali appeared side by side. At some point, they may well have resided in a stack of identical double-image woodcuts, in an edition that would have been cut into two parts, allowing for double the profit for Nrityalal Datta. He would sell them as souvenirs to pilgrims who had traveled to the Kalighat Temple to worship a fearsome goddess.

Art in print, Volume 6, Number 3, September–October 2016

- See, for example, B.N. Mukherjee, Kalighat Patas: Paintings and Drawings of the Kalighat Style, 2nd edition (Calcutta: Indian Museum, 1998).

- “The Battala engravers had challenged the Kalighat patuas [pat painters] to a competition in which the former could score on the latter by virtue of faster production and cheaper prices. While the Kalighat paintings cost an anna each, a Battala print could cost ‘a penny plain and twopence coloured.’” Nikhil Sarkar, “Calcutta Woodcuts: Aspects of a Popular Art,” in Ashit Paul, ed., Woodcut Prints of Nineteenth Century Calcutta (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1983), 32.

- Ibid., 34.

- Mark Baron wrote to me in an email (July 4, 2016): “All Kalighat paintings, woodblock prints, and Indian Hindu god and goddess prints [the lithographs] were printed on a very acidic wood-pulp paper. All were framed in the worst possible way, with cardboard or wood behind the paint/print, and pressed against the glass (so no airspace for the sheet to dry when it’s humid). And, in Calcutta the average humidity, year-round, is 70%, but during the monsoon months it’s 100%. So all are disintegrating. But what makes the woodblock prints special is that they were not only printed on a very bad acidic paper, but on a super thin very bad acidic paper, so the ones that weren’t mounted have crumbled.” Add to this the probability that, as Purnendu Pattrea writes, “[they] were priced so low that their patrons may have considered them not worth treasuring and preserving,” and you have a recipe for extinction. Purnendu Pattrea, “The Continuity of the Battala Tradition,” in Paul, Woodcut Prints.

- For an account regarding this change of taste, see Partha Mitter, “Mechanical Reproduction and the World of the Colonial Artist,” Contributions to Indian Sociology 36, nos. 1 & 2 (New Delhi: Thousand Oaks & London, 2002), 1–32.

- Sarkar writes that there is just one firmly dated woodcut, from 1871. They are almost never dated, so most estimates are made from indirect written sources.

- See Baron’s account of the collection’s origins in Richard Davis et al., Gods in Print: Masterpieces of India’s Mythological Art, A Century of Sacred Art (1870–1970) (San Rafael, CA: Mandala Publishing, 2012), ix. This is the first comprehensive look at the lithographs and is illustrated with many prints (though not exclusively so) from the Collection of Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté. For an earlier account of the collection’s beginnings, see Faye Hirsch, “Seeing God in Prints: Indian Lithographs at the IPCNY,” Art in America, Mar. 11, 2009, artinamerica.com/news/seeing-god-in-print-ipcny-1/ (accessed July 4, 2016). Baron and Boisanté’s website is omfromindia.com.

- Pranabranjan Ray, “Printmaking by Woodblock up to 1901: A Social and Technological History,” in Paul, Woodcut Prints, 93.

- From the Dhyana mantra of Daksina-Kali from the Kali-tantra, quoted in David Kinsley, Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1997), 67.

- Dhyana mantra of Guhya-Kali, ibid.

- Besides the Baron/Boisanté Kali, the others are located as follows: the Indian Museum, Kolkata; the Victoria Memorial Museum, Kolkata; the Museum of Indology, Jaipur; the Delhi Art Gallery (a commercial gallery); the Museum of Folk and Tribal Art in Gurgaon, outside Delhi (otherwise known as K.C. Aryan’s Home of Folk Art); and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

- The Nrityalal Datta print, much damaged, at the Delhi Art Gallery, is very close to Baron and Boisanté’s Kali. One difference is in the details of the baubles hanging from Kali’s upper arms, which dangle before the lower arms in front of her long black hair. In Baron and Boisanté’s Kali, the baubles are missing, as is the black hair behind the two lower arms, where the space is blank. Either the baubles and hair were carved away within the same block in a later printing, or this print was made from an entirely different block. I have not seen an image for the third Datta print, but according to Baron it is reproduced in the museum’s publication Masterpieces of Indian Folk & Tribal Art, by Suhashini Aryan (Gurgaon, India: K.C. Aryan’s Home of Folk Art, Museum of Folk, Tribal & Neglected Art, 2005); in an e-mail to me dated July 3, Baron writes that it is “identical” to theirs.

- Baron and Boisanté have never been able to see the Kali at the Indian Museum in Kolkata, so cannot testify to authorship. And they have not in years seen the one they were initially enamored of at the Museum of Indology, so they cannot ascertain authorship there, either. When they returned to the museum it had been taken off display, and they have been unsuccessful in their attempts to make an appointment to see it again.

- Pattrea, “The Continuity of the Battala Tradition,” 77.

- Imma Ramos, “The Fragmentation of Sati: Constructing Hindu Identity Through Pilgrimage Souvenirs,” DAPA (The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts) 27 (September 2015): 26.

- See above, n. 10.